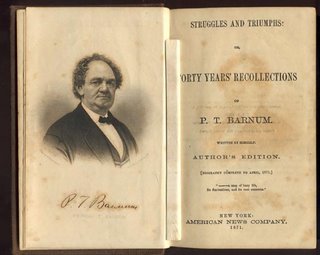

Autobiography is one of the primal literary forms. And one of his subcultural products, circus autobiography, turns to be a most entertaining literary form. Hundreds are been written, most of them even forgotten (for example, very few of us ever put eyes on a a copy of pamphlets such, say, The Chief Incidents of the non-professional and professional career of Holtum, the Dane surnamed The Cannon King. Related by himself, 1855). Reading them, we will never be able to separate the truth from facts concerning the whereabouts of authors being in their first occupation high wire walkers, whale exhibitors or flamboyant impresarios around the world in 80 years. But we just don’t care. We just ask them to absorbe us in adventures closer to Munchausen and Gulliver than to our usual order of things. From Althoff to Zavatta, Conklin to Van Amburgh, we just enjoy them. Otherwhise, for what reason Barnum’s literary effort was said to be the most read tome of his times after the Bible?

Once established the nobility of the genre, we are now happy to salute a new book in the perfect line of this tradition: Gerry Cottle’s Confessions of a Showman. Just fresh from press, I was surprised to discover it a couple of weeks ago on the main shelves of London’s best bookshops, so I treated myself with a copy (for those deprived by the pleasures of such a fisical encounter, Amazon.co.uk wil provide).

Cottle is a famous contemporary circus impresario. If considered in the proper contest (the British society and the circus international milieu 1970-90), his life and achievements have a quality not less interesting than precedessors, and illustrious waxers of themselfes, as Barnum or Sanger.

In circus history, the 70s are known for the rise of experimental circus. But in those same revolutionary years, the classic circus ind

ustry knew a generation of unexpected kids from the “ordinary” society trying to revamp the traditional concept and the logic of the classic families, even without subvert their conservative aesthetics. They did that just opening their own big tops, doing brilliantly, and briefly reaching a leadership in the industry: as Siemoneit and of course Roncalli in Germany, Jean Richard in France, Castilla in Spain, the Felds, Binder and Vargas in the USA, etc. And Cottle in England.

ustry knew a generation of unexpected kids from the “ordinary” society trying to revamp the traditional concept and the logic of the classic families, even without subvert their conservative aesthetics. They did that just opening their own big tops, doing brilliantly, and briefly reaching a leadership in the industry: as Siemoneit and of course Roncalli in Germany, Jean Richard in France, Castilla in Spain, the Felds, Binder and Vargas in the USA, etc. And Cottle in England.From one side, Cottle’s book follows all the necessary rules to be a classic in the genre: the “run away with the circus”, the humiliating education and the consequent acceptance in the world of saltimbanques, the following rags-to-riches adventures of becoming an established showman, the struggles and triumphs of such a mission, without disappointing the reader’s expectations of Far East trips, tamed lions and flamboyant press stunts.

From another side, there is more.

If the literary nature of impresarios autobiographies has the epic form of an almost superhuman hero taking his own feats seriously, Cottle turns upside down the concept: is he human. And he tells it with a lot of good self-humour. According the title, the winning key of the book is his form: a real confession more than a simple account.

It must be historical accepted that for a certain time Cottle was able to became, from nothing, the most powerful British circus man. If he tells us his story acknowledging his own talent, he is much more aware of all his weakness. And that is the the thing that makes the book great: as in the best of drama or literature, he invite us to identify in a normal human being. Ok, he tells us about enterprising feats of epic proportions (from risking money he doesn’t have to fly a complete circus to Iran few days before revolution), and he is more than proud of it. But his show is not Ringling or Roncalli, and he knows it. He is egocentric and megalomaniac in their same way, and he knows it. And he tells it to us with an irresistible sense of humour. God bless, finally, a circus impresario that for a time doesn’t take the circus seriously! And he finally breaks the law of “clean world for familes” with his intimate, frail, human, sometimes tragic but always passionate stories about sex and drugs, inestricables from his most serious vice and addiction: the showbiz itself.

What is also great, is the vision of the circus in its times. The honest and intelligent point of view of a man protective of a traditional vision, but at the same time able to investment ranging from a cheesy Circus on Ice to a hip Circus of Horrors, and so intelligent to recognize a genius like Pierrot Bidon as show director; fighting hard for the right to have animals but brave to attempt the first human circus. Foreseeing as fews the upcoming potential of Russian and Chinese shows. The book is written and produced for the general audience, and not for some obscure, celebrative press for fans. This opportunity is well played, showing in an entertainig way the nature of relationship between circus and society, his potential of interaction with the medias, his struggles with contemporary bureaucracies. And how deep is today the gap between the notion of traditional circus and the contemporary culture. And what is great of Cottle, is that as impresario he didn’had the professional tools of seven generations in his back, neither the intellectual education of the modern circus creators. He just did it, well aware the limits of both.

In one of the interviews for the launching of the book, he delivered a quote that impressed me:

"I think circus is at a terrible crossroads. Traditionalists have got to get out of their minds that animals aren't ever going to come back -- the majority of the public don't want them any more. And the new circuses are trying to impress each other, not audiences."

No comments:

Post a Comment